During the advent of printmaking, many artists and creators alike struggled with branding their own work with rulings going in favor of the creation's right to be made, and not the creator's right to make. Does this sound familiar to today's plight against the advent of AI?

This is what the new exhibition at Wisconsin's Chazen Museum of Arts is trying to explore, by showcasing the answers that a Medieval European printmaker found during the advent of the printing press. "Art of Enterprise: Israhel van Meckenem's 15th-Century Print Workshop" will allow viewing from Dec. 18 until March 24.

In its essence, the exhibition follows the lifework of Israhel van Meckenem, and consequently, his impact on the concept of branding identity during the 15th century. Meckenem's prolificity mainly occurred during the latter half of his life by mass-producing Old Master Prints and engraving his own art, which usually depicted a German's everyday life.

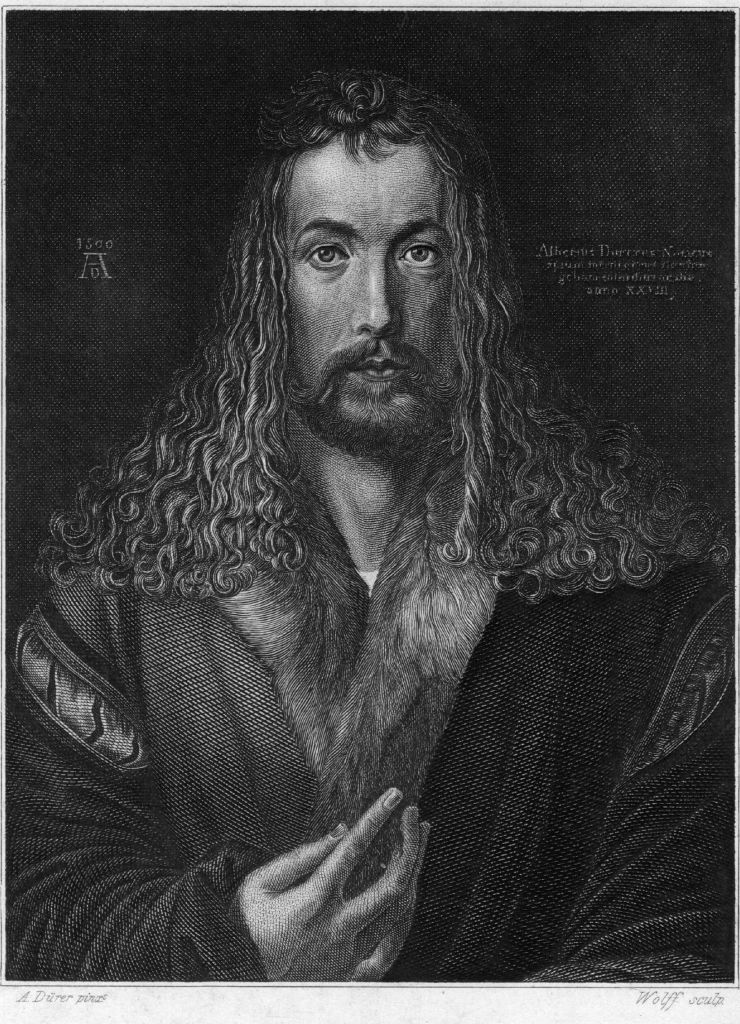

The show will display over 60 historical objects that are relevant to Meckenem's lifework, and will also include engravings from his contemporaries like the German engraver Master ES and German painter Albrecht Dürer.

Israhel van Meckenem's Experiments on Identity and Trademarks

According to a statement by the exhibition's curator, James R. Wehn, Meckenem is an exceptionally interesting Medieval European printmaker when seen through the lens of today's concepts about creating.

"He does some things early on in the history of European print that makes him special," Wehn shared.

In particular, Meckenem was considered to have pioneered the printed self-portrait, which according to Wehn, is an act that exhibits the level of "autonomy" that early printmakers had when it comes to self-promotion. Additionally, the museum will display a double portrait of Meckenem and his wife, nicknamed "an ancestor of the selfie."

The most interesting about Meckener, however, is how he experimented with trademarks by using his own identity. Meckener was also the first printmaker to sign his own work using elaborately ornate text that mimics those that can be found in illuminated manuscripts, the legal documents of the time.

Humorously, Meckener had signed works that would be considered plagiarized by modern-day standards. Wehn stated that Meckener would find the engravings of other artists, copy them, and sign the work with his own name.

"Modern audiences will find the paradox amusing," Wehn claimed.

Read Also : Censored Artwork of Banksy, Picasso, and Others Feature in New 'Museum of Forbidden Art' in Barcelona

The Medieval Race to Distinguishing One's Work

Meckener's contemporaries eventually realized that they too needed to differentiate their works from other printmakers. This concept was echoed by Albrecht Dürer whose life had a striking resemblance with Meckener's

Wehn maintained that Meckener had copied four of Dürer's works, although historians aren't sure whether or not Dürer himself was aware. That said, Wehn raised some indications that Dürer was cognizant of Meckener's work, having copied Meckener's prints as well, but the German painter did change a lot of the work drastically.

Dürer did try to prevent further plagiarism from happening by appealing to the Holy Roman Empire and he also complained to the local governments about other artists copying him. The rulings however allowed the copying of the image itself, but not the trademark identity of the artist.

"What this tells us is that, at that time, the concept was that labor and materials were valued. And so, it's okay to plagiarize. But it's not okay to forge," Wehn shared.

All in all, for Wehn, Meckener's career, and Dürer's for that matter, was one of the earliest roots that advanced copyright and intellectual property conceptualization.